The Campaign for Public Education

This month's edition is a departure for this report, It was written by John Cartwright, and originally intended for internal use in the labour movement as a case study of coalition building during the late Mike Harris years in the early 2000’s. John is the former president of the Toronto and York Region Labour Council. In Ontario, as other provinces, political action by labour is generally divided into labour councils relating to municipalities including school boards, the OFL to provincial government and CLC to national and international situations, but political struggles don't often fit neatly into these categories.

During the Harris Eves regime 1996-2003 education was radically underfunded by a documented $1 Billion, forcing local school boards into painful cuts, as property tax was simultaneously, uploaded by the provincial government which meant total financial control of education.

During this tumultuous period John Cartwright was in the key position to speak and act for all of labour in the Torontp and York Region. He also put LCT&Y on the map in critical areas of Green Jobs, Apprenticeships, Public Transit, and equity within and beyond the labour movement.

Since 2019 John has retired from Labour Council and now Chairs the Council of Canadians.

The Fight for Public Education

Working people have always known that public education is a crucial foundation for a just society. The Toronto & York Region Labour Council has always included a call for investment in public education, ever since its founding in 1871. It has been a constant theme in the Labour Council’s political work.

A fierce struggle to defend publicly funded education took place in Ontario between 1995 and 2003, during the Mike Harris Conservative years. In the face of drastic budget cuts, attacks on unions, and the centralization of control over the entire school system, a new community labour coalition was born in Toronto: the Campaign for Public Education (CPE).

The strategies adopted by the coalition helped build huge public support for the education fight. The CPE’s efforts, combined with similar ones across the province, caused education to become a key factor in the Conservative government’s defeat in 2003. There are lessons to be learned.

CONTEXT

In 1995, the Mike Harris Conservatives were swept to power under the banner of a “Common Sense Revolution.”. They rapidly implemented massive changes to all aspects of government operations, including cutting welfare rates, cancelling subway-lines and social housing projects, repealing equity legislation, stripping worker rights and ending transit funding. Once elected, the Harris government immediately announced widespread cuts to all public services, including schools, in order to pay for hefty tax cuts.

Harris ruthlessly pursued policies modeled after Margaret Thatcher’s political program in the United Kingdom. The Harris government issued edicts designed to force local school boards and municipalities to essentially carry out its dirty work - slashing programs, abandoning disadvantaged communities, and turning on their own employees. Minister of Education John Snobelen famously said he wanted to create “a useful crisis” in education in order to set the stage for dramatic restructuring.

EDUCATE, ORGANIZE, RESIST

In response to the so-called Common Sense Revolution, the Ontario labour movement started mobilizing to show business leaders that there would be an economic cost to this political onslaught. Most of Ontario’s unions embraced the slogan “No Justice, No Peace” (the concept that without justice, there would be no peace) and 60,000 provincial employees hit the picket lines for the first time. The provincial labour movement set out to hold a series of city-wide general strikes. Toronto’s Days of Action were held on October 25 and 26, 1996. Schools shut down, along with most unionized workplaces, and 250,000 workers and their allies marched to Queen’s Park under the slogan “Educate, Organize, Resist.”

Still, the Harris Conservatives continued to impose dramatic, regressive changes at every level. By 1997, a billion dollars had been taken from education in Ontario. Significant cuts were made to a range of programs and supports, local schools were closed, class sizes were increased, and a “one size fits all” approach instituted, all of which affected students’ learning conditions and meant that schools had less ability to address local needs.

Education unions mobilized across the province to oppose these changes, while students, parents, elected Trustees and local community groups all raised their voices. But the Conservatives didn’t stop. Indeed, they went further down their destructive path than anyone had imagined they would go.

They took away the ability of local School Boards to levy taxes and centralized all school funding. The independent role of elected trustees was targeted by reducing trustees’ annual salaries to $5,000 and cutting their access to school board benefit plans. School principals were removed from the bargaining units. The Conservatives’ Bill 103 forced a merger of the Metropolitan Toronto municipalities into a new megacity. Bill 104 did the same to the corresponding Boards of Education.

TEACHER PROVINCE-WIDE FIGHTBACK

In response to a wholesale attack on teachers’ working conditions and their bargaining units, the teacher federations launched an unprecedented two-week political action. A mass rally at Maple Leaf Gardens to protest Bill 160 set the stage for 126,000 members to walk out of their classrooms on October 27. It was the largest teachers’ “strike” in Canadian history, and a remarkable show of solidarity across the province. By the end of the second week their organizations had experienced a baptism of fire.

In communities large and small, teachers were never isolated. Parents draped schools in green ribbons and many came out to picket lines to show support for their kids’ teachers.

Importantly, while the mass mobilization of members did not stop the legislation, it created a new culture of activism. People who had entered the profession for the love of learning had been thrust into the front lines of class struggle. Their unions were transformed, and soon formally joined the mainstream labour movement, including local labour councils.

“Thank you teachers for standing up for the 3 D’s – Decency, Dignity, Democracy” Poignant message on a banner on a house overlooking the teacher picket lines in 1997.

THE MEGA-BOARD

On January 1st, 1998, the new Toronto District School Board (TDSB) came into being. It had 300,000 students, 21,000 employees and 600 schools, and was to be governed by 22 part-time Trustees. It had the most diverse student population in the country, with many students coming from immigrant families whose first language wasn’t English. A wide selection of community services – from childcare centres to adult learning - were not covered by the new funding formula. The Board’s funding was eviscerated, and, within months, dozens of school closings were announced.

Employee organizations were forced to restructure and merge into distinct bargaining units – Elementary Teachers (ETT), Secondary Teachers and Professionals (OSSTF), the Skilled Trades Council, and Local 4400 of the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), which represented over 500 occupations. Each had to bargain new collective agreements and with most of the trustees going along with the imposition of cuts, the stage was set for conflict. On February 27, 1999, CUPE Local 4400 went on strike for two weeks to try to stave off massive outsourcing and contract concessions. The new union had focused its efforts on engaging members, training stewards and activists, carefully building its internal structures and preparing intensely for a walkout to defend its membership. The strike ended with a victory on key items, while other issues went to arbitration. Not everything was won, but the spirit of resistance laid the groundwork for future organizing, and for Local 4400 to play a central role in the education fightback to come.

SERVICES COST MONEY

Despite widespread opposition, the Conservatives were re-elected in June 1999. With a renewed mandate, Harris continued to drive his agenda. The school funding formula established by Queen’s Park left the TDSB woefully under-resourced. Reserves were being drained to keep school buildings from crumbling and services from eroding. Parents organized in every part of the city to try to protect the services and programs for their children. Swimming pools in the old Toronto Board schools became a target, and a new coalition sprung up to defend them from closing. Shelley Carroll and other parent activists published the widely read newsletter Boardwatch, while unions created brochures featuring photos of Conservative MPP’s faces to highlight their complicity in the damage done to their local communities.

Parent leaders became vital public voices in challenging the provincial dictates. In the fall of 2000, the labour movement endorsed a number of these parent champions to run for the Toronto District School Board. The OSSTF urged its members to donate “Ten Bucks for a Better Board” to endorsed candidates, raising money and volunteers for key campaigns. Unions from many other sectors got involved at both the municipal and school board level to help elect progressive voices to public office.

A NEW BOARD

Newly elected trustees, including Kathleen Wynne, Shelley Carroll, Sheila Cary-Meagher, Bruce Davis, Paula Fletcher and Nelly Pedro had campaigned on fighting cuts. They soon joined with veteran stalwarts Irene Atkinson, Sheila Ward, Stephnie Payne and Elizabeth Hill to form a progressive caucus, and the stage was set for a major battle over Board operations and the upcoming budget. A new initiative to open up the budget process for public input would prove to be a crucial strategy It included the creation of popular material by the TDSB entitled “The Real Costs of Public Education” which explicitly challenged the provincial approach.

Over the next year, the progressive side lost many of the contentious issues by a difference of two votes. Director of Education Marguerite Jackson’s demand that CUPE 4400 support workers take a wage freeze, while teachers received salary increases, led to a gruelling four-week strike by CUPE members in the spring of 2001. Back-to-back strikes are never easy, and the union was very careful to choose tactics that wouldn’t alienate the public. The union decided to set up only information pickets at elementary schools, allowing teachers to enter the schools to conduct classes, and it shut down a limited number of secondary schools each day with boisterous mass pickets. Support from teachers was solid.

The strike mobilization and community outreach deepened the culture of resistance to the overall Conservative agenda. The education unions organized within their memberships to build a strong network of well-informed advocates for public education. Union leaders John Weatherup (CUPE 4400), Jim McQueen (OSSTF) and Martin Long (ETT) collaborated closely as each union committed to being present and visible in every workplace and community. A constant flow of information went out to stewards, branch presidents and other activists to help them engage and partner with parents.

COALITION-BUILDING

An effective slogan was crucial for this common effort, and “Give students what they need to succeed” reflected what most Canadians believed should be the role of publicly funded education. The slogan helped define the narrative of the ongoing alliance work. The scope of the work was far wider than just program funding or staff numbers. It included classroom curriculum and democratic decision-making, to reflect local priorities.

In October 2001, after months of organizing, a coalition came together under the name Campaign for Public Education (CPE}. It was made up of students, education workers, teachers and parents, including the Toronto Parent Network, the Toronto Federation of Chinese Parents, and the Parent Community Network. Cathy Dandy (Toronto Parents Network) and Murphy Browne (Parents of Black Children) became the public spokespersons for the coalition, and Dandy soon emerged as a key voice on education issues. Veteran CUPE leader Rob Fairley facilitated regular meetings of campaign partners and oversaw strategic campaigning. Parent activist Cassie Bell anchored CPE’s outreach and support work.

NORTH ETOBICOKE VICTORY

In 2001 an unexpected opportunity arose to change the balance of forces on the Board. North Etobicoke Trustee Sam Basra was charged with immigration fraud. He had created fictitious employment-offer documents for would-be immigrants from India, including some offers on TDSB letterhead. In August he was convicted of seven counts of fraud, and he should have been removed from the TDSB. But he was a leader of the Conservative riding association and a close ally of the Harris government, so they delayed taking action. It was left to parents to file legal proceedings to seek his removal. In December the courts ruled that he should refrain from attending Board meetings and, in January 2002, Basra finally resigned.

The Labour Council had been working with community groups in North Etobicoke, and it initiated a process to help choose the most electable candidate. The Rexdale Cross-Cultural Committee included representatives from the Caribbean, Somali and South Asian communities. Stan Nemiroff had been the runner-up in the past election. A retired professor, he lived downtown but ran with labour’s support against Basra. This time, while he registered for the by election, he let people know he would step aside in favour of a local candidate if someone had a better chance to be elected.

The candidate search did not identify a suitable alternative, and Nemiroff was endorsed by labour and the education unions. The process had created a sense of trust with key newcomer communities in North Etobicoke and they mobilized behind Nemiroff. The alliance with community activists also bolstered the credibility of the labour movement with their own members from those same communities. Some unions had incredible diversity among their membership living in the area; the Steelworkers alone had over a thousand, mostly Black and South Asian members in the ward.

The Labour Council framed the election as an opportunity to challenge the entire provincial Conservative agenda, and affiliates responded with a real sense of purpose. Industrial unions booked off activists from their jobs and did mail-outs to their members. Municipal unions got heavily involved, the Ontario Public Service Employees Union (OPSEU) set up a phone bank, and the education unions canvassed their members in the ward. Money was raised for signs and literature, and the Labour Council’s executive assistant Julius Deutsch helped manage the campaign.

On the other side, Conservative forces came in behind former Etobicoke Mayor Bruce Sinclair. They knew they were in trouble on the education file and did not want to risk losing power at the TDSB. But, on election night, that is exactly what happened. Nemiroff won with nearly double the votes of Sinclair. With trustee numbers now evenly split, the die was cast for an epic battle over funding.

GIVE STUDENTS WHAT THEY NEED TO SUCCEED

With school board trustees across the province raising concerns about the cuts, the provincial government brought in rules that would hold trustees personally liable if a Board decided to go into deficit. This was an unprecedented level of intimidation of elected officials. Still, in a number of cities trustees considered taking that risk to defend the programs their communities needed and deserved. Trustees networked through the Ontario Public School Boards Association (OPSBA), and the TDSB progressive group met as a caucus to explore options.

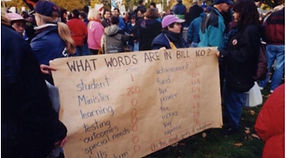

Mike Harris resigned in April 2002 and was replaced by his Minister of Finance, Ernie Eves, while Liz Witmer became Minister of Education. That spring the Campaign for Public Education launched a massive information campaign that included lawn signs and brochures demanding fair funding. Union members helped deliver signs to school councils, parent groups and labour activists across the city, and soon the eye-catching green design was seen in every neighbourhood. Progressive trustees continued to caucus together and to meet with the CPE, while students organized in high schools.

In his May Throne Speech Eves announced the appointment of an Education Equality Task Force, led by Mordechai Rozanski, to review the province’s education funding formula which had not been updated since 1997. But the government still insisted that all school boards pass a balanced budget based on austerity and cuts, even though the vast majority of school boards went on public record to object to this approach. The Minister extended the deadline for passing a budget, but the Ottawa, Hamilton and Toronto boards were steadfast in their opposition. In July, leaders from a dozen school boards held a summit in Hamilton to help bolster the determination to resist.

DEFYING THE LAW

The stakes were huge for the trustees: – they faced the possibility of a $5000 fine, of being barred from holding office for five years, and of personal liability for the deficit. Still, the progressive caucus remained determined to take on the fight.

At the July 31st TDSB meeting, the vote was split 12-10, and the Board did not pass the “compliance budget” which would have been $90 million less than the aspirational “needs based budget.” The vote on a deficit defied the law and triggered the province to suspend the democratic role of trustees. Witmer had sent accountant, Al Rosen, to review the expenditures of Ottawa’s and then Toronto’s school boards. His report laid the blame on the trustees rather than on the flawed funding formula, and Rosen recommended that both school boards be put under supervision.

UNDER SUPERVISION

In August 2002, Education Minister Witmer appointed supervisors to take over the public school boards of Toronto, Ottawa and Hamilton. The government took out newspaper ads claiming their action was necessary because the trustees were wasteful and negligent. Former Metro Councillor Paul Christie was named to oversee all the TDSB’s spending and programming.

Board meetings were only allowed to make recommendations to the supervisor, and the progressives members debated whether or not to boycott the meetings or to continue meeting without any power. They decided to utilize the meetings as a platform for community and labour voices to be heard.

The school board takeovers prompted a massive public debate. The cuts suggested by Al Rosen were widely seen as damaging to the quality of education, not just for working-class and immigrant communities, but even for better-off families. The voices raised against the supervision kept repeating the single demand: for funding to “give students what they need to succeed.” People from all walks of life interpreted that slogan in a deeply personal way, depending on their own experience. It was a powerful message that the Conservatives could never overcome.

The Labour Council reached out to all its affiliates in Toronto with a fightback strategy, asking local unions to invite guest speakers to their meetings and to pass a resolution to campaign on the issue within their own memberships. The Campaign for Public Education placed full-page ads in weekly community newspapers. The ads featured picture of each Conservative Member of Provincial Parliament and a call for constituents to hold their own MPP, not just Ernie Eves, responsible for the crisis. This was an important tactical move that immediately put pressure on the entire Conservative caucus and laid the groundwork for their defeat a year later.

While all this was happening, the Rozanski Task Force on the funding formula was holding hearings. Labour representatives turned out in force with well-researched submissions, asserting that quality public education is a cornerstone of a democratic and just society. When Rozanski reported in November, his findings vindicated concerns around the inadequacy of provincial funding. According to some estimates, his suggestions would have added nearly $2 billion to overall education funding, including money to address the maintenance backlog of crumbling schools. But the Eves government was in no hurry to make the money flow.

CUTS AND RESISTANCE

TDSB Supervisor Paul Christie raised some cash by selling schools to the Catholic Board, but he aimed most of his financial cuts at support staff and programming. Fees for community use of schools were raised to the point where some sports teams could no longer book fields. The position of Youth Counsellors was eliminated, with dire consequences for students from marginalized communities. An entire campaign emerged to defend school pools from closure, while graphic pictures of decaying buildings prompted media attention on the safety of staff and students.

Every step of the way, Christie met dogged resistance from TDSB unions and their community allies. CPE continued to mobilize public opinion on the loss of democracy while reaching out to groups that would suffer from the results. It held training seminars for school council participants and sponsored rallies protesting the supervisor’s actions. CPE ads and postcards challenged the closing of outdoor education centres. Progressive trustees devoted countless evenings to meeting with school councils to keep parents informed about the impact of budget decisions. Education unions invested significant resources into supporting parent involvement in CPE, and the diverse voices around the decision-making table created a genuinely collective approach.

The Conservative agenda created turmoil at the Toronto Catholic Board as well. The administration locked out the Catholic Elementary Teachers in an attempt to impose major concessions. While Catholic parents were not as well organized as the TDSB parents, they also came to see the Conservative government as the root cause of the problem.

As Conservatives dropped in the polls, they tried to put on a softer image. By June, Christie announced a reversal of the plan to cut continuing education programs that served 30,000 adult learners. Resistance was paying off.

The Labour Council developed a comprehensive 2003 municipal electoral strategy that gave greater emphasis to school trustees than ever before. The ambitious plan focused on intensive canvassing in every ward and engaging many diverse communities in building momentum for change. Drawing from the experience of the Nemiroff campaign, each union identified members by ward postal codes and set out to communicate regularly as part of an unprecedented state of election readiness.

The provincial election was set for October 2003, one month before the municipal vote. Unions everywhere mobilized their members for a massive turnout to throw the Conservatives out. The Labour Council printed thousands of “Fire Ernie Eves” postcards on different issues, for affiliates to mail out to their members. The answer to the question “Want to do something good for education?” (or other key issues) was: “Fire Ernie.” The postcards were wildly popular.

Every Conservative MPP in Toronto went down to defeat. Kathleen Wynne was elected to Queen’s Park (later to become Premier) and one of the first acts of the new Liberal government was to remove the provincial supervisors of the three school boards.

The momentum continued in the November municipal elections. Torontonians elected labour endorsed Mayor David Miller along with Shelley Carroll, Paula Fletcher and CUPE 4400 leader Janet Davis to City Council. Trustees Irene Atkinson, Elizabeth Hill and Sheila Ward were acclaimed without opposition. Progressive candidates were now the majority at the Toronto District School Board and they set out to rebuild a system that had been under siege for eight years. The fight to “give students what they need to succeed” would enter a new stage, with the Campaign for Public Education playing a central role. Investment in serious organizing had helped make history.

CONCLUSION

The education fight didn’t take place in a vacuum. The City of Toronto itself was reeling from the massive downloading of provincial responsibilities, ranging from social services to transit operations and social housing. Social justice groups campaigned on a wide variety of issues, challenged Mayor Lastman’s agenda of tax freezes and austerity, and defeated the attempt to privatize the city’s water system. There was a spirited public dialogue about investing in early learning and childcare, along with a growing realization by sections of business that the Common Sense Revolution had serious downsides.

In June 2002 the Toronto City Summit gathered together influential civic leaders to call for renewed vision of Canada’s largest urban centre. One area of focus was public education, a priority that labour representatives had forcefully brought to the table.

The fight to “give students what they need to succeed” stands out in our history because of the high level of commitment education unions made to help organize and resource a popular mass movement, while at the same time engaging with their members to a degree seldom seen in public sector union struggles.

This education story is about the dynamics of struggle, and how workers, community activists and elected representatives can learn from and support each other. In those trying times, all of us were essential to the outcome. The keys to success were vitally important: developing a bold strategic plan, constantly checking on its implementation, and ensuring that the tactics chosen help lead to actual victories.